"I always likened joining a band, to joining the circus, or a funfair. All involve travel (running away?), and finding your people (who don’t ask too many questions?)"

Interview by Emily Waller

Drummer, icon, survivor.

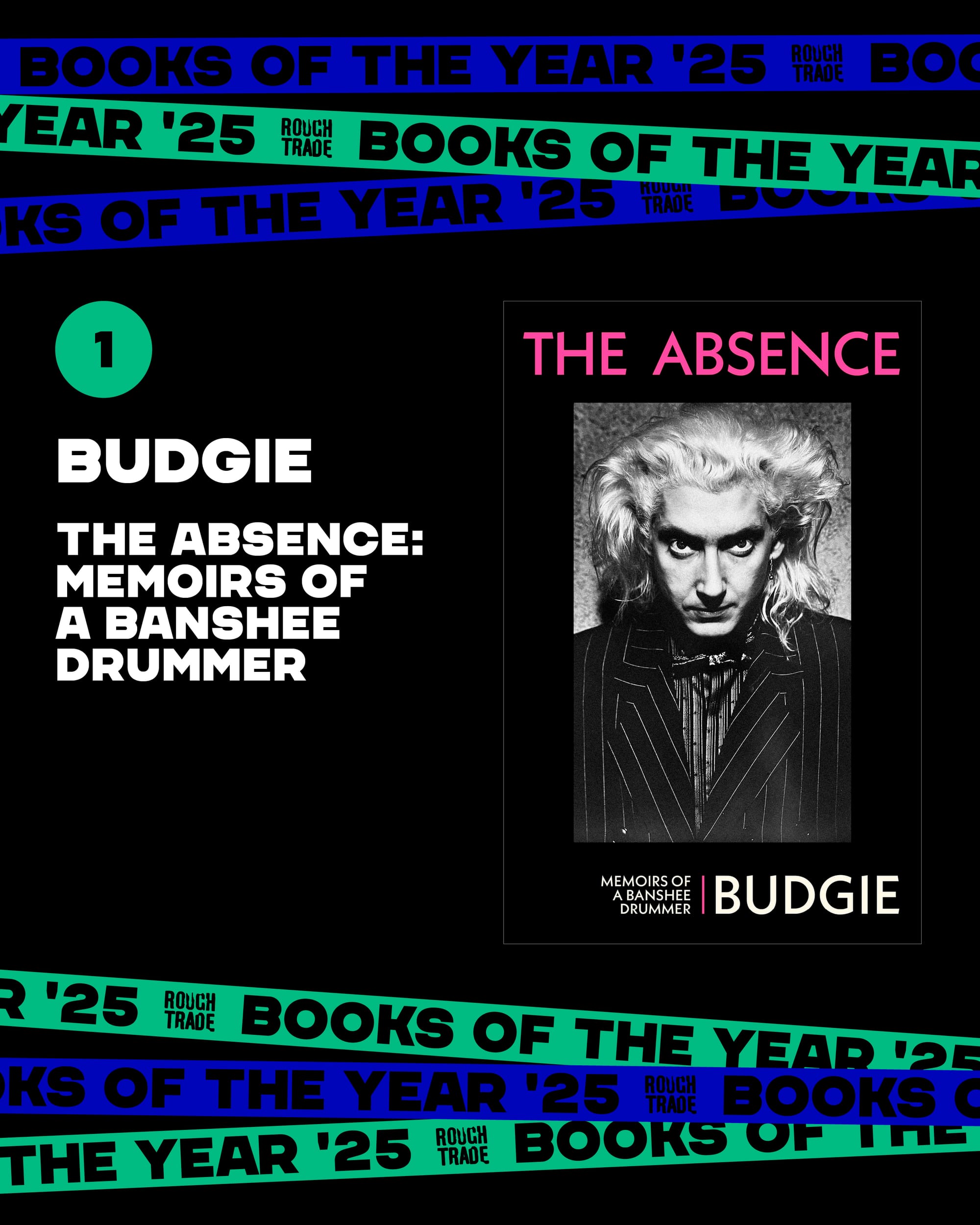

One of the 80s goth-pop scene’s most mysterious figures, Budgie (Siouxsie and The Banshees, The Creatures) digs deep to present to page a deeply personal and beautifully written story of darkness, glamour, brilliance and burnout. A memoir that feels as rhythmically alive as his drumming, this is the tale of someone who lived, breathed, and survived the chaos. Reflecting on creativity as salvation, and what it means to tell your own story truthfully, Budgie’s candid view leaves an impression that lingers long after the final page.

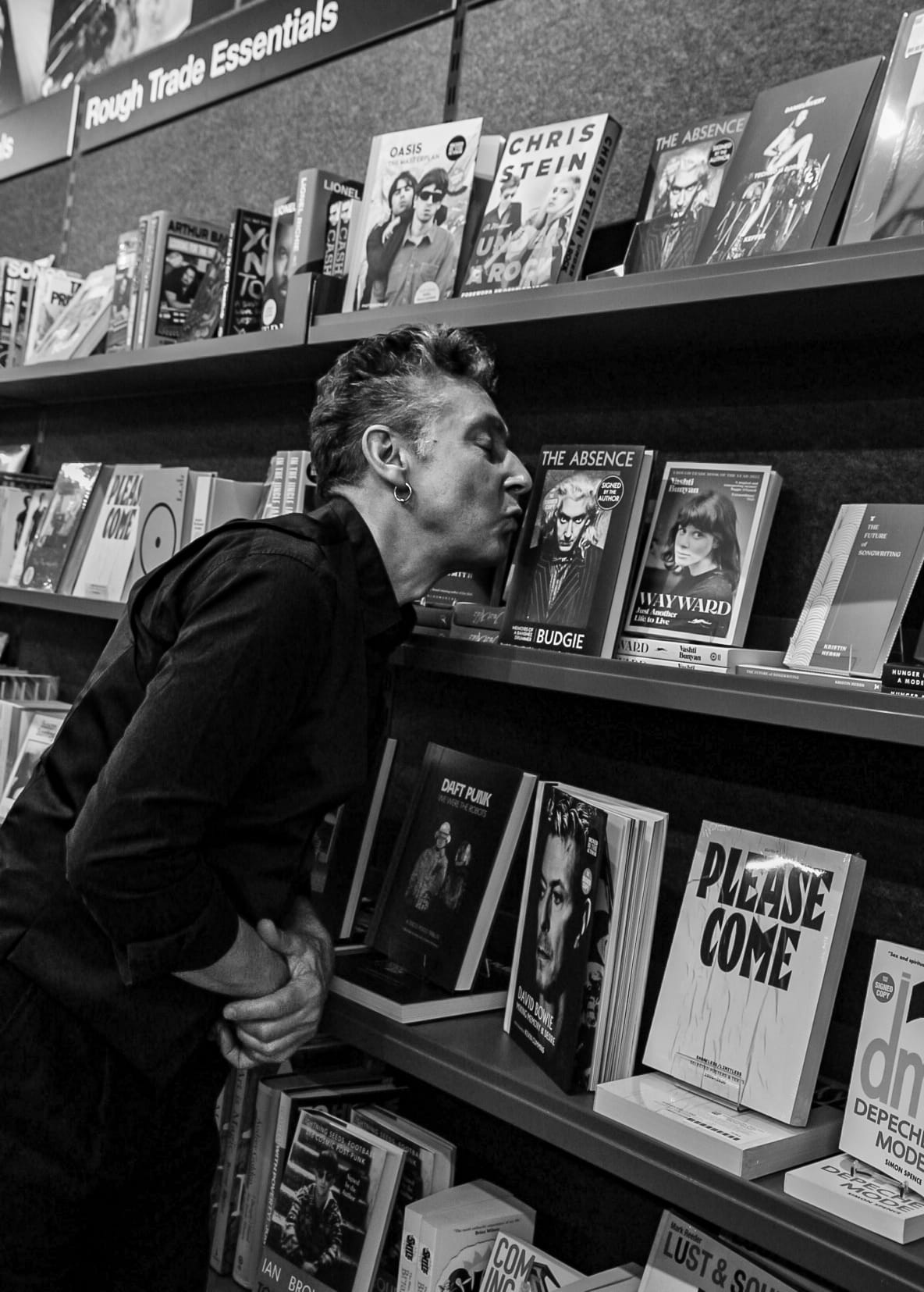

The Absence is not just a standout memoir, it tops our Rough Trade Books of the Year list for 2025. Emily caught up with the acclaimed drummer to mine the Berlin-based musician for insight to his writing process, dissecting the past and creativity as solace.

Photos by Phil Bluhm

The late ’70s post-punk scene is often painted with wild stories, press caricatures and nostalgic retellings. How do you feel that mythology compares with your lived experience, and were there things you wanted to set straight in your book?

The memories and myths are always embellished and exaggerated, and always different depending on who is doing the retelling. The odd thing is that the actual event or situation being retold, was often so unscripted, so spontaneous, possibly risky and mostly unrepeatable, that the memories don’t do justice to the chaos and chance of the actual experience. Memory is usually too neat and logical. In my book I attempt to say how it was for me, how my experiences affected me. If someone says, ‘that’s not how it happened’ I can only set it straight, to be my version of events.

Lydia Lunch describes your memoir as “a travelogue of self-discovery.” When you look back at your younger self, what surprises you most about the person you were then?

In a video on YouTube, my younger self is stalking about backstage after an early Siouxsie and The Banshees gig. I am struck by my certainty, by my drive and my cocky outspokenness. Presented with my own voice and image, I don’t recognise myself. If the camera doesn’t lie, I have to accept this version. The biggest surprise is that I was not as one dimensional as my memory leads me to believe. In later filmed interviews I am shocked to see how that once individual character has been subdued, tempered, become a collective we, no longer a fiery I.

The honesty in The Absence is searing throughout. Was it always your intention to lay it so bare, or did that openness develop as you moved through the writing process?

The prologue is one of the first things I wrote specifically with the book in mind. I had written many versions of many other incidents but the prologue and the epilogue were my litmus tests. I couldn’t just repeat what happened - I had to recreate and relive those scenes. I had to go back there and be an active participant, not just an observer. Through that process the scenes began to write themselves, as an amalgamation; of many events from other times, to better convey the mood and effect of the particular moment being described.

Is The Absence reflective of the style of memoir you yourself enjoy reading? And were there particular books or voices that shaped how you wanted to tell your own story?

It was more that I knew what style of memoir I didn’t want to write. I didn’t want to describe endless tours and associated incidents. I didn’t want an album by album chronological journey and I didn’t want to end it in post break up bad blood or litigation. That said, I knew it wasn’t going to be a bedtime story. I love Viv Albertine’s memoir, Clothes, Music, Boys, it gave me courage and confidence. I admire Rupert Thomson’s memoir, This Party’s Got To Stop. His poetic descriptions engage all the senses and there’s a frisson of danger in his reveal of family tensions. I was blown away by Carmen Maria Machado’s In The Dreamhouse. Firstly the title looked familiar - it was just ‘A Kiss’ away from a Banshees’ album title. In its construction and invention however, lies the work of a maestra. Machado’s powerful use of the 2nd person present point of view throughout In The Dreamhouse I shamelessly borrowed for the epilogue of The Absence. More Alfred Hitchcock than Tony Hancock. Ironically, a lot of humour in Hitchcock, a lot of pathos in Hancock.

“Maybe a young person’s trauma acts as a foundation stone in a wall to shut out the world.”

History could track the belief that some of the best music and art comes from flawed individuals. In your experience, can imperfection, struggle, or damage be the catalyst for brilliance?

I haven’t attained satisfaction, certainly not brilliance - (still time!), but my mother’s premature death certainly provided a catalyst for me to begin seeking it. One of the recurring questions, as I introduced the people I met along the way was, do damaged individuals attract each other, and together create better art? Does the denial or alternatively the investigation of personal trauma, provide a conduit for creativity? Or is the creative seed always present - the blocking out of trauma enabling a protected and protective space for creativity to flourish undisturbed. A place where nothing else matters. The painter Frank Auerbach, whose family perished in the holocaust, said that he rarely thought about those events. Maybe a young person’s trauma acts as a foundation stone in a wall to shut out the world.

Loss is a recurring force in your story - your mother’s death, fractured relationships, the toll of addiction. How did making music and collaboration distract you from those absences? How much of a teacher has creativity been throughout your life?

I always likened joining a band, to joining the circus, or a funfair. All involve travel (running away?), and finding your people (who don’t ask too many questions?) Creativity has taught me many things. To be true to myself, and to trust the inner voice, but only if there are no substances influencing that voice. Alcohol, amphetamines and a few things beginning with the letter C. When I quit alcohol; and I did many times before stopping for good 30 years ago, creativity didn’t disappear, it went into overdrive. Photography, music, drawing, ideas, I couldn’t sleep. Unfortunately neither could the mind, and I was not equipped to handle the feelings, emotions and needs that had lain dormant for so long. Creativity came to the rescue again but this time it manifested in my trying to be creative for others rather than just for myself.

How did writing about your relationship with Siouxsie shift your own understanding of that chapter of your life, both personally and artistically?

There’s a quote from the Spanish poet, Federico García Lorca, “To burn with desire and keep quiet about it, is the greatest punishment we can bring upon ourselves.” It perhaps gives some insight into the much perhaps over-romanticised aspect of forbidden love. Could it be that self-imposed secrecy serves to prolong the initial period of lust and desire, thus delaying the stronger emotional connection needed for true love? Writing about my personal and professional relationship with Siouxsie, gave me a better understanding of why we worked so well together professionally and why we, or certainly I, lacked the emotional maturity needed to develop a deeper long term commitment - outside the magic of the music.

How differently do you think things might have played out if social media and the internet had been prevalent during your time as a young artist? When you look at the industry today, do you ever find yourself comparing your own experience and that of your peers, to the young, emerging bands on the alternative scene?

In 1970s Britain, information was at best slow on a national level and always out of date and out of touch internationally. Being a big fish in a small pond was easy in small towns and even in the larger cities outside London. London was the place to get known. Yet even London became small very quickly. To make any impact in Europe meant annual touring, a lot of currency exchange, and endless border checks. America required annual touring, many telephone interviews and endless visits to local radio stations. The impact of all this time consuming and costly activity would have reached a few hundred, maybe a few thousand people. With the launch of MTV in 1981, artist’s videos could be viewed by millions of people every day. But it quickly became clear that even MTV wasn’t going to help every small band to give up their day-jobs. Social media and internet distribution of music may help a few already high earners to earn more, but it doesn’t support the local alternative scene which now has even fewer small live venues in which to hone its skills. I think the internet would have negated the shock and surprise of the Sex Pistols arriving to play in Texas, and The Clash playing several sold out shows at NYC’s Palladium theatre. It was still possible to take the world unawares. There is no comparison. Greater visibility via the web doesn’t really help emerging bands, when there are thousands more small fish, all vying for attention in a very accessible global pond.

As a reader yourself, do you think memoirs about musical heroes can change the way we hear their music? And if so, is there anything you hope readers might hear differently in your own work after reading your book?

I don’t think a musician’s memoir can alter how we hear their music. It’s interesting to read the usual biographical stuff on offer, but I doubt that even a work as enormous as Francis Bacon - Revelations cannot change the way we see Bacon’s paintings. Similarly a musician’s memoir may give some insight into the lyricist’s words or even the sound of the band, but the music itself still stands alone. I think a successful memoir from a musician should likewise stand alone and not be dependent on prior knowledge of the music created. Together they may well enhance each other. I read the late Mark Lanegan’s powerful memoir, Sing Backwards and Weep and after reading a harrowing ordeal he went through to make an appearance on TV, I had to find the performance to see if he really made it. I still haven’t heard much of the band’s music. Mark Lanegan’s book didn’t turn me into a fan of Screaming Trees, but I marvelled at his recall and his writing. The book stands alone.

Rough Trade Book of the Year 2025

Budgie - The Absence: Memoirs of the Banshee Drummer

Limited signed copies!