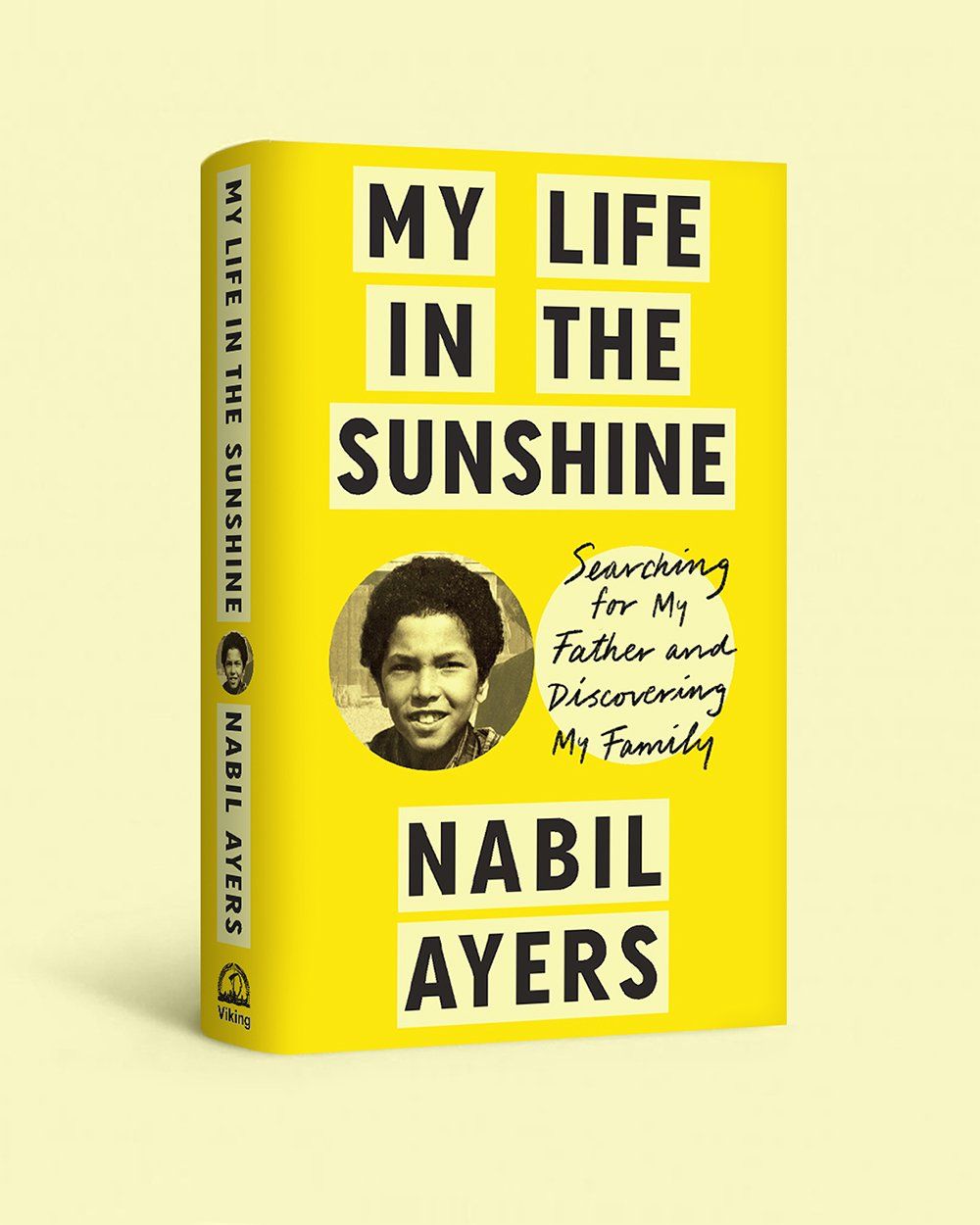

With his new memoir, My Life In the Sunshine, Nabil Ayers looks backwards with clear eyes and brilliance as he recounts his bi-racial upbringing in Salt Lake City, playing music and running a record store in a booming Seattle scene, the lingering effects of his jazz legend father’s absence.

My Life In the Sunshine is a stunning recollection of formative musical experiences and familial introspection. To celebrate this highly anticipated book, we're thrilled to share an excerpt, courtesy of Penguin Random House, along with a conversation between Nabil Ayers and the president of Sub Pop Records, Megan Jasper.

Read the excerpt below, then head over to the Rough Trade NYC IGTV to watch the fascinating conversation.

Signed copies of My Life In the Sunshine are available for purchase.

Excerpt: My Life In the Sunshine

20.

Easy Street

Along with many UPS graduates, I moved forty-five minutes north to Seattle after my senior year in the summer of 1993. My friends were in law school and graduate programs, and working for big local companies like Microsoft or Boeing. But I didn’t share their post college goals. I wanted to be in a touring band, and I knew that any kind of real job would prevent that from happening. And as much as I loved my record company internship and had long- term goals to work in the music business, even that felt far off—secondary to playing drums for a living.

While my friends shopped for suits, moved into nice apartments, and took me to steak dinners on their shiny new corporate credit cards, I worked for a temporary agency, where I earned enough to cover my living expenses and had enough time and energy to let everyone know that I wasn’t looking for a job, I was looking for a band.

Steph from PolyGram set me up with a job interview at Easy Street Records, a great record store in the West Seattle Junction, an antiquated, old - American downtown district near the house I shared with Jason and three other roommates. Matt, who owned the store, was surprisingly young—in his twenties—and affable with a quiet confidence. I’d never worked in a record store, but I accidentally nailed the interview when Matt explained to me, “We’re not just a cool record store, we sell everything from Metallica to Roy Ayers.” I told Matt that Roy was my father, and I started my new job the next day. That was the first time my father had ever done something for me, even if it was unintentional.

Music was more exciting than ever, and I had even more access to it at Easy Street, where the senior staff constantly exposed me to previously unfamiliar artists. I worked alongsideKirsten, a wonderful, pale goth with a black bob who once explained to me the sensuality of menstrual blood while blasting Nick Cave’s Let Love In. Stephen, the manager who sang in a band that had almost been signed and who wore a puffy white shirt under a tight black vest, played the goth band Fields of the Nephilim every day. New CDs arrived daily, and we listened to everything from Portishead’s gloomy, haunting debut to Gling-Gló, the twenty-four-dollar import-only jazz vocal album by Björk.

West Seattle seemed like a separate city from Seattle, even though it was only a ten-minute drive from downtown. There were some very rough parts—my roommates and I each paid $154 per month for our five-bedroom house near High Point, where there was gang activity. West Seattle also had areas on the water around Alki Beach, where some Seattle rock stars chose to live, removed from the city.

Soundgarden’s singer Chris Cornell sometimes arrived at Easy Street right at 9:00 p.m., when we were scheduled to close. He would start shopping as the store was clearing out and nicely ask whoever was working to let him stay just a bit longer so that he could shop in private.

Pearl Jam’s singer Eddie Vedder shopped at Easy Street during our regular hours. I was working once when Eddie came in and bought our entire Who section — about fifteen CDs. He wore a tight green ski cap and stood in line, impatiently fidgeting with a childlike grin on his face. The kid in front of him bought a Pearl Jam CD and had no idea who was standing in line behind him— this caused Eddie and me to exchange a knowing smirk. He paid with hundred-dollar bills, then bolted out the door. I watched his green cap bounce down the street until it was out of sight.

My roommates and I often piled into Jason’s navy blue Isuzu Trooper to see shows at RKCNDY, the Off Ramp, or one of the many other rock clubs in Seattle. To save money, we learned which bars sold which beers and we filled a cooler in the back of the Trooper that was stocked according to that night’s venue. RKCNDY meant Budweiser tall boys. The Crocodile Cafe meant Sierra Nevada pale ale bottles. We made trips to the car to restock our jackets between bands. My cheap rent, Easy Street guest list privileges, and nonexistent bar tabs made for an inexpensive, carefree post-college life in Seattle.

Because of my experience at PolyGram, Matt gave me the role of label representative at Easy Street. I was responsible for dealing with the various record label representatives who called and visited the store. It was my job to make sure the poster displays were current and relevant, ensure we had in-store play copies of every new release, field phone calls when labels wanted to know how many copies of an album we’d sold, compile and send out the weekly sales charts, and take care of all guest list requests for the staff at upcoming shows.

It was the heyday of the CD, when relatively unknown alternative artists like No Doubt or Alanis Morissette could quickly sell millions of albums. Seattle and Easy Street had become very important in the national picture, and I was right in the middle of it. Suddenly I knew everyone. Label people often called the store from New York and Los Angeles. I spoke to the trade magazines and I was quoted in CMJ, Hits, and Album Network. If I wanted a personal copy of a new album, all I had to do was ask. I met every hot new act from Liz Phair to Veruca Salt to Everclear. I ate and drank for free all the time, and was invited to every show and every party. Though I wasn’t playing in a band, Easy Street was a dream job where I could sense my acceleration into the music industry.