"It’s hard to wrap one's head around the fact that the things we made mean something, the way someone else’s music means something to me."

Interview by Emily Waller

Photos by James George Potter

Illustration by Iris McConnell

Brooklyn, NYC’s Nation of Language featuring Ian Devaney (lead vocals, guitar, synthesizer, percussion), Aidan Noell (synthesizer, backing vocals) and Alex MacKay (bass guitar) released their third, meticulously crafted record and our Album of the Year in September 2023. Strange Disciple follows previous albums A Way Forward (2021) and Introduction, Presence (2020) and is an expanded exploration of their signature synth-pop sound, brilliantly realised across 10 hypnotic tracks that explore and evoke the chaos of infatuation, all testament to the band’s evolution over the last 3 years.

When we speak at Rough Trade East during the UK leg of their European tour, what is so brilliantly evident is the love they have for their craft and their almost dovelike wonder at realising the impact of their artistic journey to date. As we close out 2023, I know Nation of Language will be as honoured by this award as we are in giving it purely because they are a family unit who have always taken great joy from their successes, big or small.

One of the very best things about working every day with people who love music is that not only do you collectively swap, muse over and revel in your individual sonic discoveries, but every so often the stars align and a mutual adoration of a singular artist washes over all. This level of endorsement is, safe to say, reserved for only very few bands and since day dot, Nation of Language have been one such example at Rough Trade. Whether it’s via their trance-inducing performances or soaring synth-pop melodies, we’re hopeful their Album of the Year crowning sees their music move a whole new legion of fans. After all, any artist’s particular ability to unite people in auditory euphoria is absolutely something worth dancing about.

Where I Am Now examines a personal journey, through music, connection and self-expression.

What are the origins of your individual relationships with music - can you each describe an early memory of a record or piece of music you fell in love with?

Aidan: I do remember my mum would tell me all the time she was intent on having a child so that she would have someone to sit next to her in the car when she was driving along listening to music. One of my earliest memories is singing Build Me Up Buttercup by The Foundations together in the car all the time. And Kodachrome by Paul Simon, on CDs that she had mixed for herself. It definitely was foundational.

Ian: There's two songs that jump out at me when I think of my early childhood: The Clash's version of Police & Thieves and the extended mix of Bizarre Love Triangle by New Order. My dad was playing those a lot and I was always dancing round the living room to them. There was definitely a lot of Clash, new wave and Bob Marley, oh and my dad has this footage of me as a toddler trying to sing Because The Night, the Patti Smith song… I don’t get the words quite right but the feeling is there.

Alex: The Clash comes to mind for sure. I was maybe 7 and I asked my parents what the loudest band of all time was. So London Calling was on pretty heavy rotation as a kid, I got to know those songs pretty well… they really made an impression on me and it’s one of my favourite albums for sure. Other artists would be Graham Parker, who is maybe lesser known now, but was pretty big in his day and my parents listened to it a lot, particularly the album The Mona Lisa’s Sister which was on the car stereo a lot growing up. English Beat as well. My parents were in a ska band together when they were younger, so they listened to a lot of The Specials, The Selecter, things like that which all made their way into my little growing brain as a child.

Aidan: I think it’s amazing that we all had parents who loved music and sort of trained us to also love music.

Aidan and Alex - you each came to the band via different paths and with varying levels of experience. What made you want to be a part of it?

Alex: More than the sound, I think it was the songs. Coming in I think you have to enjoy playing the songs and believe in the songs. If you want to be in a band for a long time you have to believe in the project. I kind of knew Ian and Aidan a bit but it’s important to be able to get along with your band mates and right off the bat there was just a seamless connection and I was happy to get invited.

Ian: We were talking to someone the other day and we were being grateful that not only us and the band, but the people we tour with, our sound engineer, our tour manager etc, we all get along so well. I think if I didn’t like someone and I had to spend 18/19 hours a day with them for months, it would be the worst job in the world. But instead it’s the best job in the world.

Alex: Yeah it could be really taxing. We’re very fortunate.

Aidan: It definitely helps that I love Ian as a partner and I want to see his goals come to fruition. Knowing that he needed someone in that moment to continue the band, when a lot of people had moved away, I didn’t want to see it end, for him, but also I really do love the songs that he writes. Lyrically they are beautiful and as a viewer I always had a lot of fun going to the shows and seeing him perform. I didn’t want to see that stop and him not have that outlet for his creativity. I don’t think we’d be together in the first place if I didn’t like the songs he wrote because when we met I was just an audience member and if he had been bad, I probably wouldn’t have tried to talk to him!

Ian (points to his face): This alone could never have carried it through.

One artist you would cite as a catalyst for your own interest in making music:

It’s hard to say for me because I never thought that I would be in a band, in which case it would be Ian, this band, that inspired me! But when I started to try and write solo music for the first time I was listening to a lot of Broadcast, who are very cool.

Aidan

Across your three albums, which process - writing, recording, performing - has challenged you the most?

Ian: I think each one has come with its own set of challenges because they were each made in very different conditions. The first record was assembled over time, whenever we could find shifts between the jobs that we were working and then we went to release that and the pandemic started. The only way that I knew how to get our music to people was to play shows and it was clear that we weren’t going to be able to do that. So then we redirected that energy into writing and recording and launched straight into making the second record, which is strange as you are making it with no end in sight as you have no idea when the world is going to open back up. That came out right when the restrictions were ending, so we didn’t get to tour it. Strange Disciple was made in-between tours, whenever we could get into the studio. I think at times it seemed overwhelming, but I think that it has helped being able to go out and meet bands and talk to people. It really boosted us and encouraged us to continue to follow our instincts when it came to being in the studio.

You toured for most of 2022 and it was kind of your first, big run post-COVID and your chance to really perform your first two albums to the growing fan base they had accumulated. What were the biggest takeaways from your experience of performing to and meeting fans in different countries?

Aidan: Honestly, it was very disorientating at first. Every time we would go to a new city for the first time, like Zurich, and we’d have a sold out show and an audience that knew the words, or at least the melodies to the songs. It was an incredible feeling. Coming to Berlin and a whole city of people…. so wild! Before the pandemic we would never sell out a show, no matter the size of the room, so it’s very bananas.

Ian: I think looking out from the stage and you’ll see people crying or making out, or both. Or people dancing, or picking a fight… It’s hard to wrap one's head around the fact that the things we made mean something the way someone else’s music means something to me. Like, I may have done something that people are connecting with. Even to say that feels like this hubris and I’m still in disbelief about any of it.

Alex: I’m still not used to it. There's still a part of me that shows up, sound checks backstage and I go peek my head out through the door and I’m amazed to see anyone out there, you know? I’ve played shows where the band outnumbers the audience, that’s just a part of it and I think you get used to that over the years. When you walk on stage and there are people there that are invested in the music that means something to you, you realise wow, it’s so much larger than just us.

Did that tour in any way evolve your idea of what Nation of Language is and what it represents?

Ian: Yeah, it really does feel like it has grown beyond what I imagined. I’m more used to the grind and not having many people there, which I think is good. If you become too accustomed to success or get that too early, I think it might mess with you a little bit. To me, we can play some big shows in big cities but we are also going into much smaller cities and playing much smaller venues and that’s the thing that I have much more experience with, so you’re just as grateful for that as the really big shows. We went to Le Touquet in France which is a town that I didn’t even know existed and it was an amazing show. There were people there and that’s wild to me, that the music can reach beyond our little world.

Did expectation feel heavy when you started putting Strange Disciple together, compared to your former two records?

Aidan: I feel like we tried not to let expectations play too much into the recording process.

Ian: I think in a lot of ways during the writing part of the process, I do close off. You are just looking for something that you think will be really cool.

Aidan: At the end of the day I feel like you are your own biggest critic, so if you please yourself, that is the base level of success.

Ian: Right. I have to be moved or excited by the songs and so once I clear that barrier, then anything can happen. You write so many songs and so much of the process is “this sucks, I hate this”. You’re just looking for the joy of “I didn’t blow it for myself”. Then you get into the recording process and my mind is partitioned into touring mode, writing mode and recording mode. And in writing mode it’s blinders on and finding something that will move me.

Aidan: So far that seems to translate to moving other people. You move me and Alex.

One artist you would cite as a catalyst for your own interest in making music:

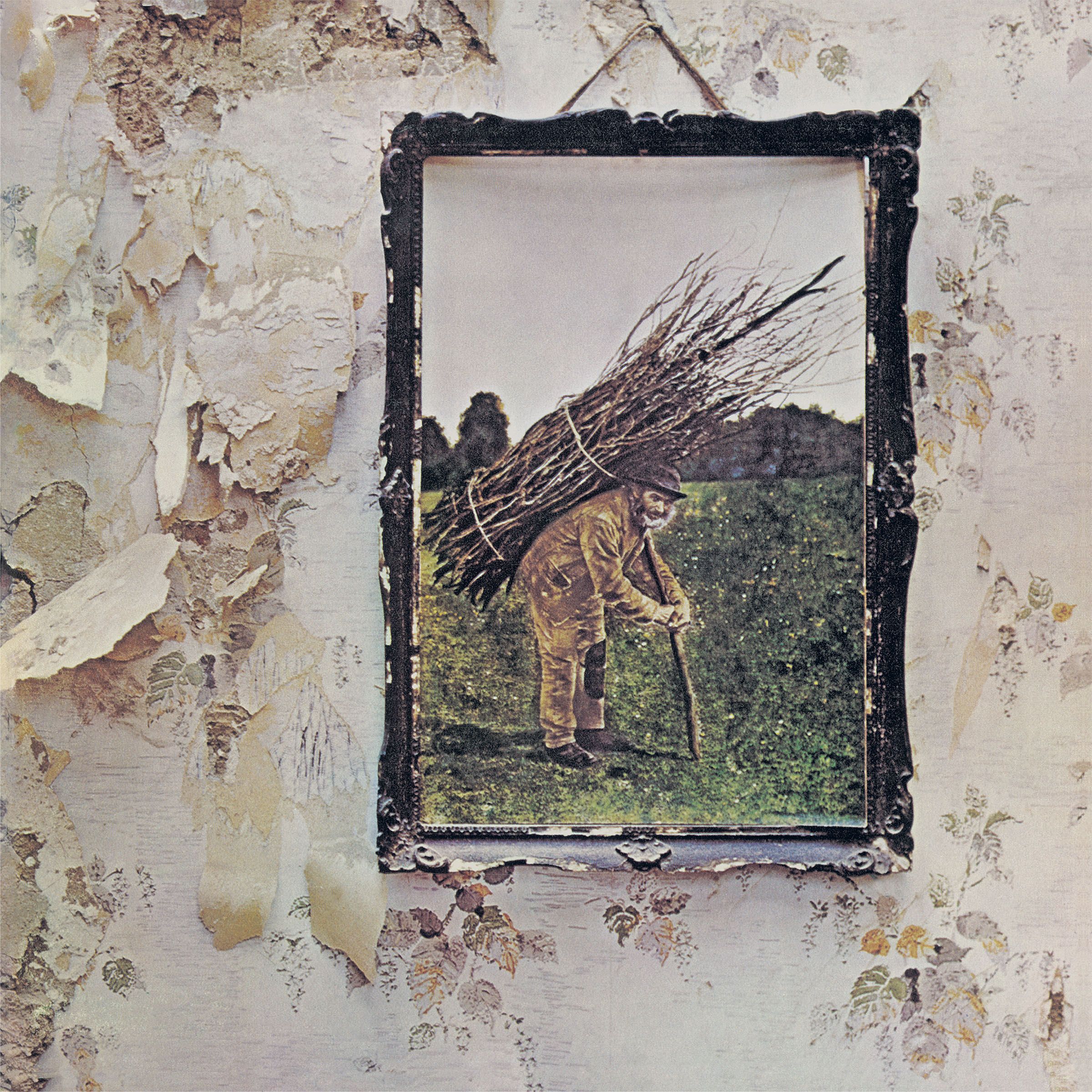

Led Zeppelin. When I first played in a band I was like 13 years old and my friends and I wanted to cover Stairway To Heaven and they were like "you can sing right?" and I was like “sure". So then that band morphed a few times and now… we’re here. I just thought Robert Plant was so cool, and still seems to be so cool, making records and being sick.

Ian

There’s this amazing sense of catharsis to your music and, certainly for me, so much of that is realised at your live shows, when that feeling is kind of transferred to the audience from the incredible physicality on display. How did you develop that performance style?

Ian: It’s definitely not in mind when I’m writing. Over the past few months we have started incorporating the new songs into the set and I don’t know how my body is going to react to this. In the lead up to a tour you’re in a very technical mindset so that when you hit the stage you can just enter this flow state of not really thinking about anything and letting your body do whatever it wants to do.

To go back to Led Zeppelin and Robert Plant, when I was very young I wanted to be this showy, classic rock frontman thing and then I found The Strokes and thought I wanna stand stock still at the microphone. But over time I just found my way into what feels natural for me, instead of trying to be anything else. Because we couldn’t play shows during lockdown, I really started to appreciate the degree to which the live performance is its own art form. It certainly made me feel more connected to people I know that are involved in dance and physicality, because it hits a whole different part of your brain and really lets you be overtaken by the music and allows your body to guide you to where it wants to go.

I read somewhere that when you relocated to Brooklyn from New Jersey you didn’t really have a network to draw from creatively - how much has that changed in the last few years and how valuable has community been to Nation of Language?

Ian: I think it’s super valuable. So it’s just me that’s from New Jersey, Aidan’s from Kansas City and Alex is from the Bay Area, so we’re kind of equidistant, 3 points straight across. I feel like Alex being in the band is a product of that community, playing shows together and finding people with whom you feel you share some kind of ethos or creative bond. Even if the music that you make isn't similar, you can just read each other in a way that is very satisfying and pushes you to want to keep creating.

Aidan: The first few years that I was in the band, or even before I was in the band, was just reaching out raw to venues asking if there were any shows that needed an opener. And then you would meet the bands you were opening for and hopefully form a friendship with them and then maybe they play again at another place and they invite you. And that’s how we made the first years of this band happen, slowly forming a network of friends.

Ian: If we can impress the bartender… So often the places we were playing, the bartender was the person booking shows and so how we started to get shows more consistently was there was a bartender who became a friend of ours and so whenever there was an opening, he would reach out. You still weren’t playing to very many people at all, but you were getting the reps of actually playing shows which was so valuable.

Alex: It takes time. We both moved to New York around the same time but we didn’t meet for another 5-6 years. I moved to New York looking for a musical community and it took a really long time, a lot of false starts, trying to find your people. We’ve all been in the city for around 9 years now and in the last 3 years it's started to make sense. You start to prove yourself to people, you don’t have to scratch and claw for every inch as much as you did at the beginning. There's lots of times that it can feel hopeless and like you’re not going anywhere, but in the last few years I’ve realised the time we spent toiling, all of that work is starting to result in something larger. There are moments for sure where you question that, where I question my own wisdom.

Aidan: At this point, when we go see someone play a show at Baby’s Alright, which is one of our favourite venues in Brooklyn, you’re seeing all these people that you’ve met over the past 9 years of your life from various scenes, and you feel like wow there really is a community that I am a part of. It’s really gratifying.

Alex: It used to feel like an impossible dream.

Ian: Well at some point you have to put in all that time and then the people that are left who didn’t quit, it’s like “I see you!"

Building a career in the independent sector, what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a band? Do you think more can be done in the industry to help grassroots artists and emerging musicians?

Aidan: We just toured in Europe with this band Mood Board and in their first year of being a band they were given a grant from the [Netherlands] government so they could play 60 shows in 60 days or something, something bananas. But they were given this money so they could have the reps, meet the venues, make connections. When we were first starting, we’d get off work, go straight to soundcheck, play a show and then wake up at 6am to start a shift. That is an exhausting way to start a band. And harder than that is having enough resources to make an album. So to see another country providing resources to give you a really solid foundation, is something…

Ian: …we’ll never get!

Aidan: It’s like a sense of admiration and jealousy all mixed into one.

Ian: The COVID lockdowns were the closest thing we'll ever get to that in America. I had been working in a restaurant and then couldn’t work in a restaurant, everyone had to stay home. So you started getting unemployment and time, and that is what allowed the band to take its next step.

Alex: And it’s not just the Netherlands. My friend Max, his band in Germany got money from the government to make a music video. I have friends in Canada that got into South By Southwest and because of that the government gave them $6k with no strings attached, an investment in culture. I think that you have to be able to develop an artistic practice and that requires a lot of time. The difficulty with New York is that once you move there you spend so much time trying to keep your head above water, your practice can be eroded. There are tens of thousands of service industry workers in NYC that are actually actors, writers, musicians, painters, and trying to balance that, it’s really inequitable. There are a lot of structural issues with it and what that creates is a lot of people get discouraged and give up. Sometimes the only people who are able to make it are those who are in a financial position where they don’t have to work, or don’t have to work as much. I think that there’s this attitude in the States that we don’t have to invest in the arts because we are already the cultural capital of the world, we have Hollywood and all this stuff. It cultivates this attitude, this classic laissez-faire of scramble for it and whoever wins, wins. It sucks, it really sucks.

One artist you would cite as a catalyst for your own interest in making music:

I think for me The White Stripes. I listened to them a lot when I was learning guitar in fifth grade and those songs were so straightforward, just guitar and drums, so I could play them together with my friend. They were accessible but also exciting.

Alex

How important would you say record stores have been in your journey and success as a band?

Aidan: I used to work in a record store. My first real job was at a place called Vintage Stock that sold used records, DVDs and video games. Working there was the perfect college experience for me, listening to new music all the time, going to shows because I knew what was happening in the scene. That was definitely part of getting to meet Ian and my life up until now, has absolutely pivoted on having that job.

Ian: In terms of inspiration, going to a record store always makes me want to go home and write again. To see other people’s creative output, I’ve always thought to have a body of work in a record store, where there’s a number of records soya can flip through is like the coolest thing to me. So when I’m at a record store it’s just instant, I’ve gotta get home, gotta start writing.

Aidan: And when you do go to a record store and see your own album in it, it’s the most thrilling feeling. You’re like yes, that is validation, someone cares! In particular, our relationship to having records in Rough Trade is really special to us as we would go all the time to the New York store. When we had our first album in physical form, we’d always take copies over.

Ian: Where this band came from, mentally, in our mind the record as an object is the final form of what we’re making. So things like album sequencing, all of the graphic aspects, every part of the packaging... what starts with just writing the songs, becomes this broader artistic project of assembling a record that people can put on and buy. I think you really learn something each time you do it. You can only fit so much on each side before the quality starts to degrade and we tend to push the boundaries of what can fit, you wanna stop right before the volume starts to go down. There’s so much that goes into just making the record that it makes you appreciate, as you walk around, that other people have to think about this too. We were talking about how on a lot of older albums the last song on the first side, or last song on a record, will be a ballad because you start to lose low end as you get to the middle of the record. So on a ballad you don’t really need low end and that’s how you can close an album without feeling like you are suffering any sound quality. It’s very cool, that the constraints of the medium inform how you assemble things.

What was the last record you bought and what is next on your shopping list?

Ian: The last one I bought was the Neu! box set, which is a huge orange monolith that has their records and then tribute records where bands would cover Neu! or include songs that were inspired by Neu! or remix Neu! and actually I got to sing backup vocals - the band Guerilla Toss have a song on that compilation that was inspired by Neu! They would be working in the same studio the night before we would go in and so they mentioned to our producer about whether I would sing on it. But yeah they are a sick band and to say my voice has been included on a Neu! compilation is very cool.

Next? Little bit of Moby, Black Sabbath and the new Slowdive, which I have not stopped listening to.

Aidan: The last record I bought was the latest Beach House record, because with all their records I just love putting them on when I'm at home cleaning, it’s the perfect music to put on and get me feeling like I should be on my feet, moving around. And I wanted to get the new Cola album Deep In View as I have been listening to it a lot on my phone, so I’d love to listen to it in record form. I do a lot of vinyl DJing, so we do have a pretty extensive collection.

Ian: Since we started vinyl DJing we now go record shopping with two minds: what do we want to put on at home and what do we feel will kill when you’re DJing. It’s not really an able that I’d ever come at it from before now.

Alex: Most recently, the Heat soundtrack. My brother’s rally into cinema and he’s got me into soundtracks. When I’m listening to vinyl, I'm setting a mood for 30 minutes/an hour and I think soundtracks and scores lend themselves well to that. My holy grail record that I’ve always been looking for is an album called Bridges by Brian Jackson and Gil Scott-Heron. It’s my favourite album of all time, it’s just perfect for any situation. It always gets me where I wanna go, amazing rhythm section.

The term ‘signature sound’ gets referenced a lot when an artist has a number of records under their belt and certainly I’ve seen a great deal of commentary on your own. What does that term mean to you and does it present any challenges as you evolve as a band?

Ian: It’s one of those things that I try not to think about so much. When I’m writing, the main thing I’m trying to do is surprise myself, you want to keep refreshing things for yourself. I think you can have a signature sound that is constantly expanding bit by bit. Radiohead to me has a signature sound, but there is a huge field of what that can mean.

Aidan: You just have to hope that people make those moves with you. You want to excite yourself and therefore excite your listeners.

Alex: I think one of then most exciting things to do is subvert expectations, but in order to do that you have to establish some sort of expectations in the first place.

Nation of Language - Strange Disciple Companion Piece

Rough Trade Exclusive green marble vinyl.