"It makes more sense the older you get, and can take you away a little from Iggy and the Stooges, as divine as that can seem, but the best, more adventurous, sensation seeking classical music can become a weapon in an attack on the commercialisation of everything, including music."

EOTN explores the records that have influenced, motivated, shaped, altered or augmented careers, projects, perhaps even lives. These are the albums that speak for a personal love of and appreciation for music; a career journey soundtracked, a memoir in songs. Obsessed with vinyl? Even better.

Photo credit: Kevin Cummins

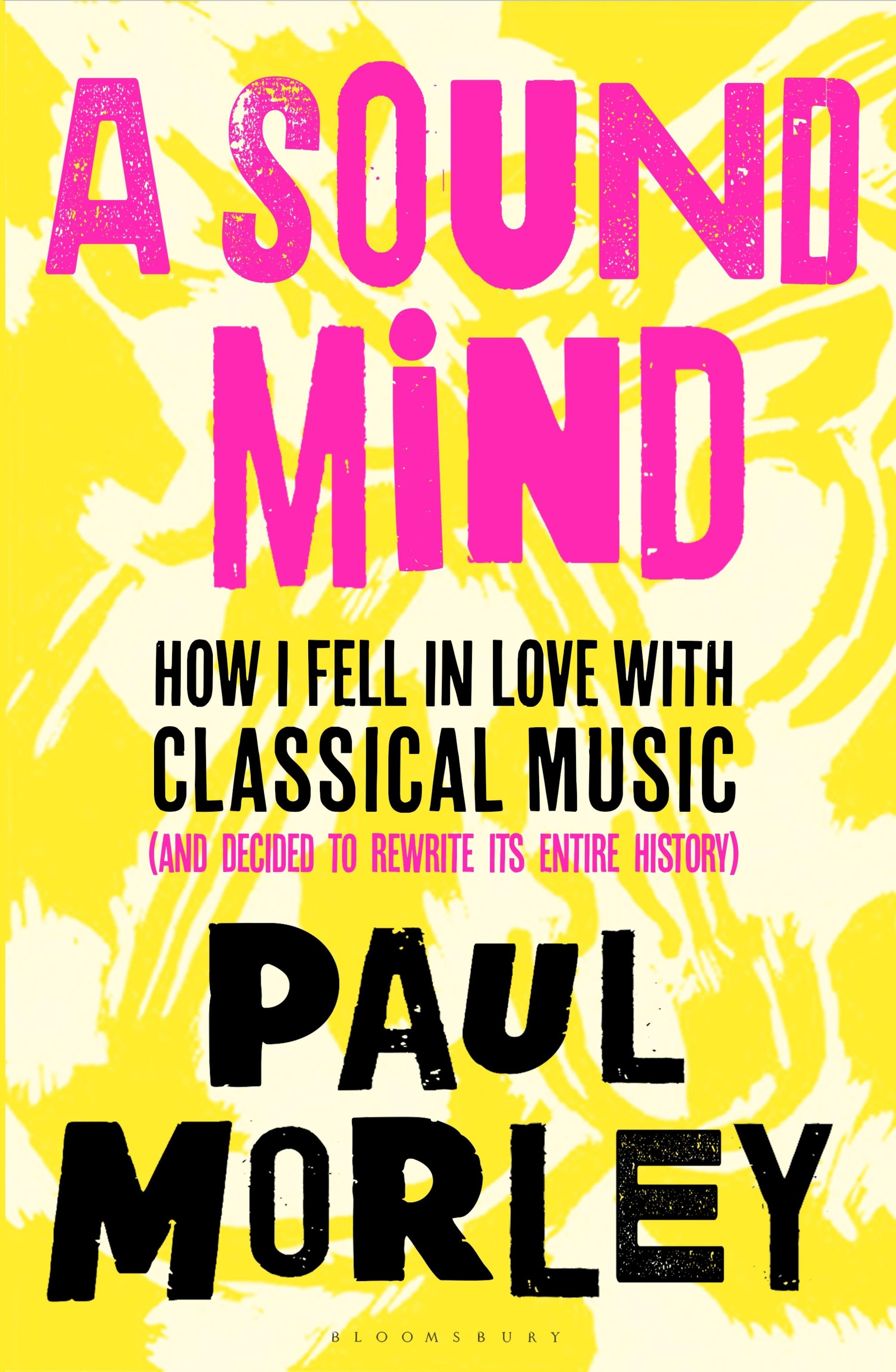

Paul Morley had stopped being surprised by modern pop music and found himself retreating into the sounds of artists he loved when, as an emerging music journalist in the 70s, he wrote for NME. But not wishing to give in to dreary nostalgia, endlessly circling back to the bands he wrote about in the past, he went searching for something new, rare and wondrous - and found it in classical music.

It is the subject of his brilliant new book, A Sound Mind, where Paul writes a compelling history of the genre, that reveals its rich and often deviant past - and, hopefully, future.

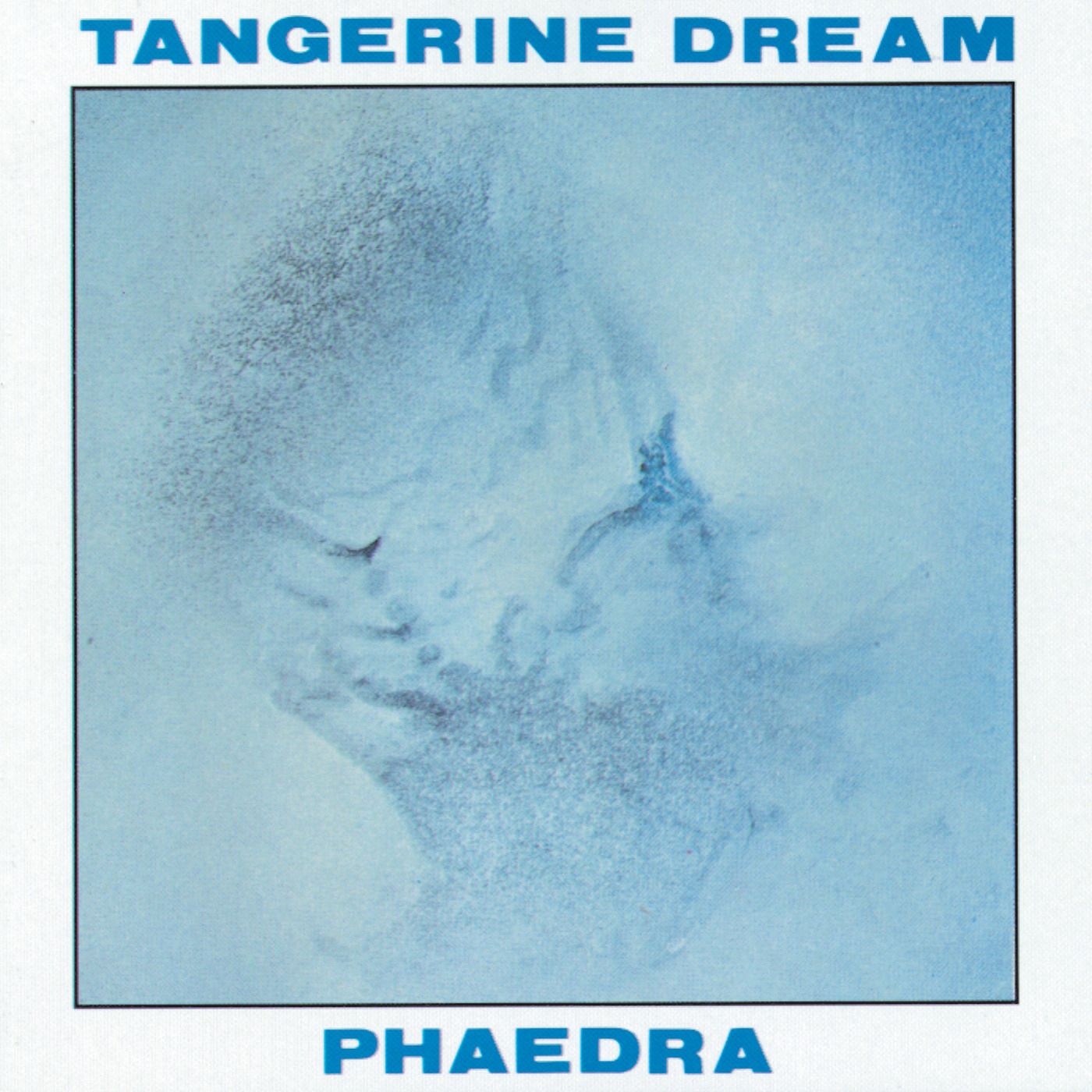

Tangerine Dream - Phaedra

There was a time, and I think in many ways there still is a time, when buying an album in an abstract silver-blue gatefold sleeve by a group with a sublime name who made dream flowing electronic music that seemed dragged down from outer space was just about as good as it got. Titles such as Mysterious Semblance at the Strand of Nightmares seemed to confirm this.

I bought this the day it appeared inside the cramped, slightly intimidating Virgin shop off Piccadilly back when that was about as far as you ventured out towards Ancoats. It was a little hint of the Northern Quarter to come decades later. A faceless German group John Peel had been playing for a while - their spaced out hyper-ambient synthesiser experiments were perfect around midnight - had signed to Richard Branson’s new Virgin label, the same year Kraftwerk released Autobahn, for some at the time another example of an avant-garde novelty music - so rock and pop music was in flux, as it opened up to this initially formless seeming dabbling, on the verge of taking a number of new directions, and Phaedra as much as anything existed as a liquid pulsing soundtrack to the changes. At the time, such uncommercial seeming ecstatic extended experiments in form actually made the album charts.

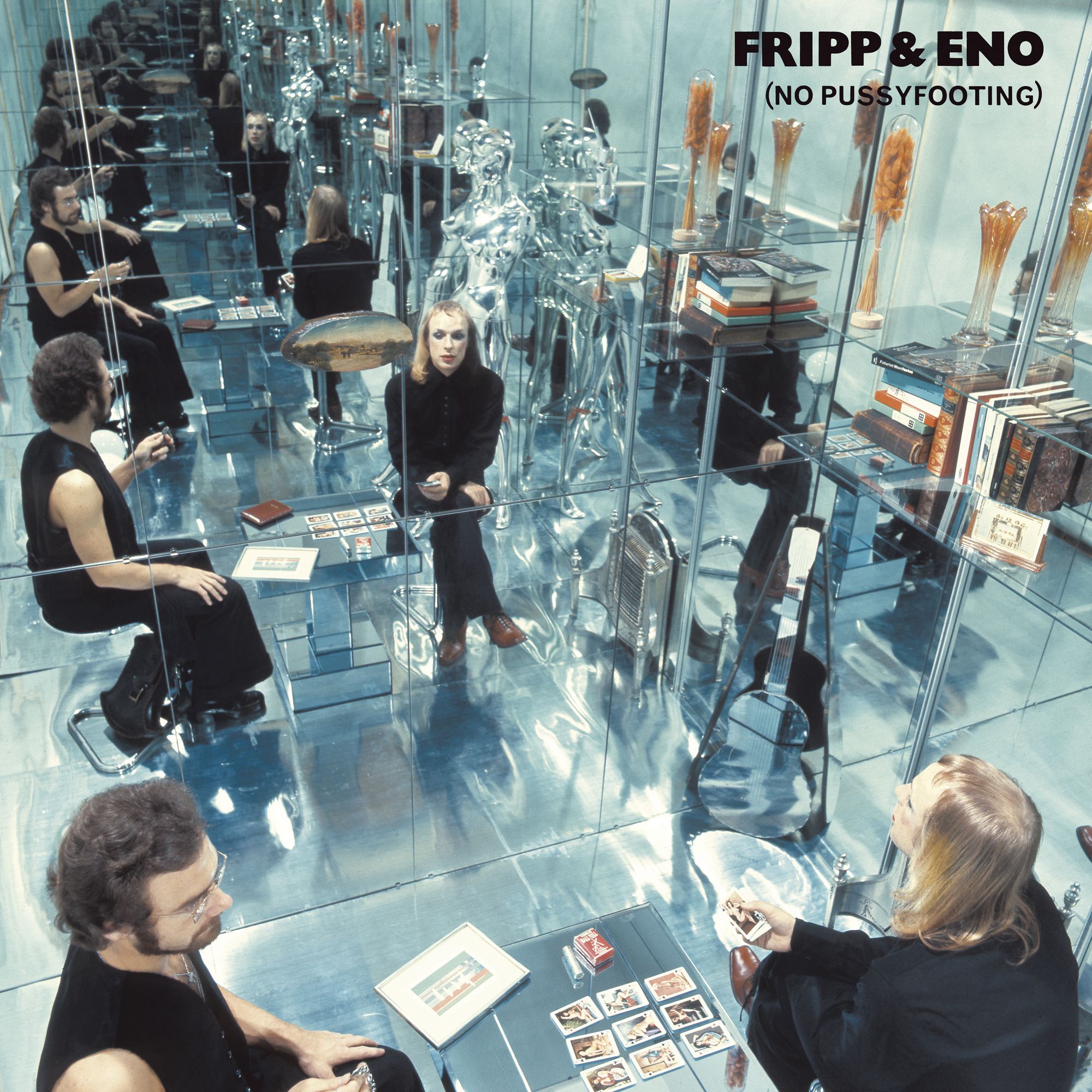

Fripp and Eno - No Pussyfooting

Following Brian Eno in 1973 out of Roxy Music after For Your Pleasure quickly led to this budget price provocation with titles like The Heavenly Music Corporation and another abstract silver-blue gatefold sleeve that was in many ways the first sound of the music itself - Fripp of King Crimson and Eno of the future sat in a room of mirrors reflecting on their reflections, which like the music seem to go on forever. Curious rock fans making the trip would find themselves in the mirrored room with a form of static drone music that it turned out had emerged from Eno’s love of the contemplative post serial American minimalism of La Monte Young and Steve Reich - Fripp’s murmuring guitar extensions looped and phased for as long as it took, longer if you played the record at half speed, because it was tantalisingly open to manipulation.

Eno had come from glam, so it seemed glam, and Fripp from prog, so it was a little prog, but mostly it was unclassifiable spiritual music that in many ways changed my life, sending me off at 16 into a universe of avant-garde music. One of those transcendent oddities that turns out to be something I’ve listened to for nearly fifty years, I mention it every few pages in my new book and if I’d been allowed would have mentioned it on every page.

Carla Bley and Paul Haines - Escalator Over The Hill

Another spectacular, radiant oddity, to this day existing in more or less a category of one, the kind of thing that was happening at the time because of what musicians like Frank Zappa, Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman and The Beatles had done with the form of the album. Pretty much the first jazz album I ever bought - even though jazz was only a small part of its glorious history of everything - possibly because it was a triple album, the sleeve was so enigmatically plain and described the record as a “chronotransduction” which appealed to the pretentious dreamer in me at the time, as did the alluring idea it was a chaotic, storyless jazz opera, and Carla Bley, the composer, controller, conceiver, conceptualist responsible to assembling this gorgeous anomaly with poet Paul Haines seemed to me to be the Virginia Woolf of jazz.

Jazz with a deviant big band swing and of course all those other things swirling in the air at the time – rock, Indian music, Avant-garde opera, Weimar cabaret, choral music, Moog experiments. A compelling compendium of where different forms of music were meeting and mutating at the time, ultimately a celebration of consciousness itself, a musical chameleon featuring guest appearances from great jazz musicians like Paul Motian, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, John McLaughlin, Roswell Rudd, the singers included Jack Bruce of Cream and Linda Ronstadt, which meant for perhaps the only time some country came close to the avant-garde.

Oh, and just to top everything off, the inevitably crazed finale ended with a locked groove effect, so that the final note droned on forever, which made the whole mad venture closely related in my mind to Phaedra and No Pussyfooting.

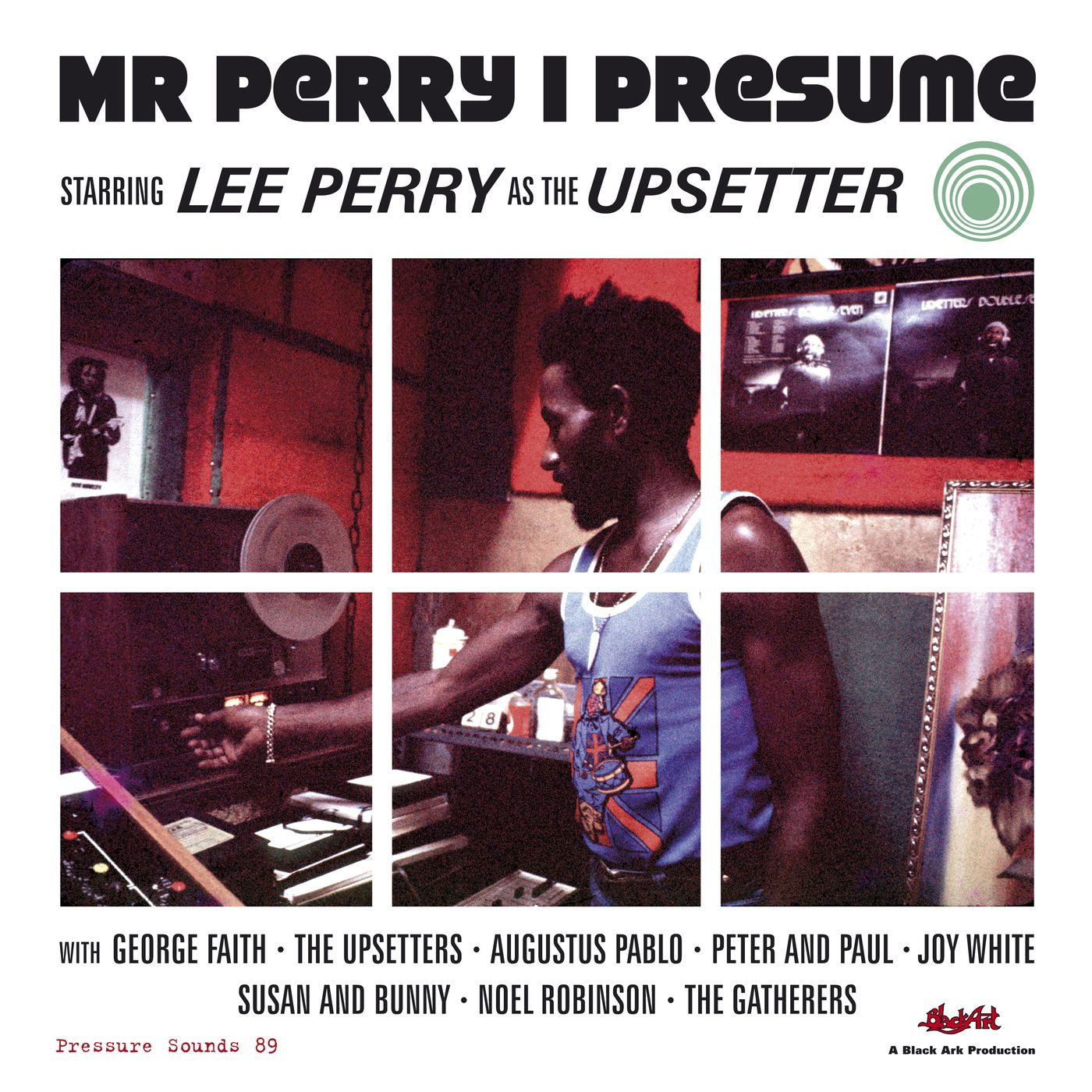

Lee Perry - Mr. Perry I Presume

It has been said that work backwards, or sideways, from everything you know about hip-hop, post-punk, electronica, trip hop and post-rock and you end up at Black Ark. This was the four-track studio in the ragged suburbs of Kingston, Jamaica, where in the early to mid-1970s, after some pivotal early ska in the 1960s and the inspired mentoring of the internationalist reggae stars Bob Marley and the Wailers Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry technically, mischievously and metaphysically remade reggae – and therefore all adventurous forms of music made, dubbed, remixed, sampled and programmed inside recording studios that followed.

For me the sonic future was rapidly opening up in the early 1970s with the likes of Tangerine Dream, Fripp and Eno and Carla Bley, and at the same time, for many different reasons, it was materialising as mind over matter, time times space, in the swooning spaced out rhythms of Lee “Scratch” Perry, whose clairvoyant deep state experiments with electronics and musical form were as extreme and exciting as those being done by Pierre Boulez, Can, Eno, Miles and Kraftwerk.

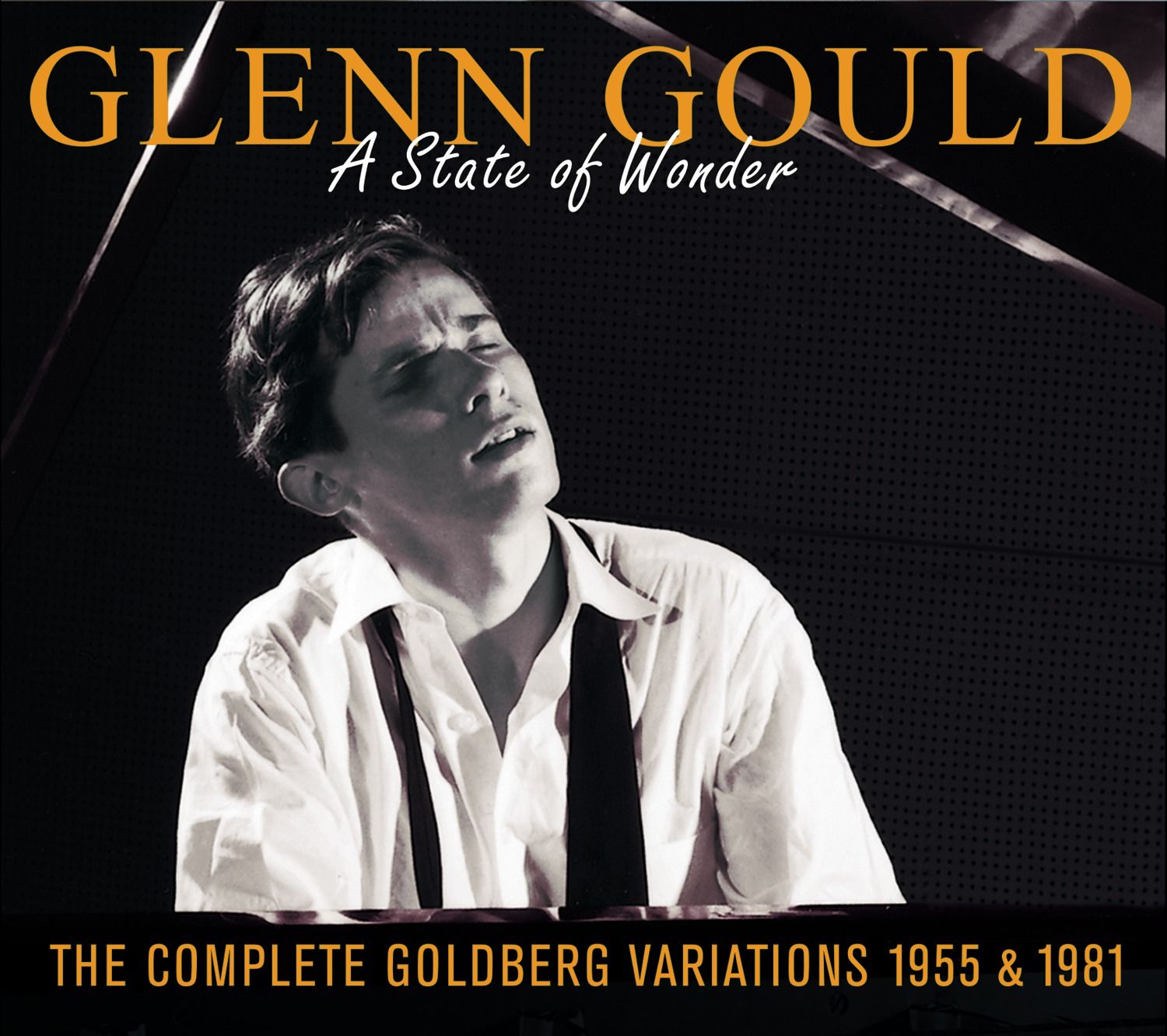

Glenn Gould - A State of Wonder: The Complete Goldberg Variations 1955 and 1981

I’ve written a 600 page book about where to begin listening to classical music if you’ve never been quite sure, featuring a few hundred recommendations – if it came down to just one way in, today I would say this boxed set of the 22 year old Gould’s astounding 1955 debut album performance of Bach’s technically demanding, esoteric, psychedelically inventive Goldberg Variations that made him a classical superstar, a vital modern figure, put with his 1981 version, recorded a few days before his death, as though that was all that was left once he’d updated, to some extent, fastidiously corrected his early masterpiece.

On the first he stripped Bach of solemnity and stiffness, making him sound completely contemporary, a matter of life and death, as energetic in its own way as any rock and roll at the time, and the second confirming how Gould transformed the way music itself is experienced. The two differently magisterial recordings framed his complicated, inspiring career, and contributed to how my relationship with classical music profoundly changed when I began to think of the music as devious, unclassifiable mental energy, as transcendent data flowing through space and creating special breathing space in a crowded, competitive world.

It makes more sense the older you get, and can take you away a little from Iggy and the Stooges, as divine as that can seem, but the best, more adventurous, sensation seeking classical music can become a weapon in an attack on the commercialisation of everything, including music.

EOTN Quick-Fire!

First record ever bought?

Ride a White Swan by T. Rex. The pop song as magic spell.

Last record purchased?

Not sure how this works now; I’ve just added the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra’s Shostakovich Symphony No.5 in D Minor to my Tidal catalogue, not essentially a record, and I have just been sent a deluxe vinyl copy of Sparks magnificently sparky A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip for making an appearance in the documentary film Edgar Wright has directed.

Best album recommended to you?

Lou Reed told me in 1979 to listen to Ornette Coleman’s Change of the Century, which of course I did.

Guilty pleasure?

Not sure there is such a thing, but for the sake of argument and more of an innocent pleasure; the happy music of James Last.

Activity most enjoyed while listening to music?

Thinking.

If the world ends let’s play out with...

Murder Most Foul by Bob Dylan.

Paul Morley - A Sound Mind: How I Fell in Love with Classical Music (and Decided to Rewrite its Entire History) is published 1st October by Bloomsbury.

DO NOT MISS: Paul Morley Live & Interactive Q&A event

Signed copies are available at roughtrade.com.